Metabolic Bacteria in the Gut Microbiome: Unveiling the Metabolic Engines Behind Gut Health

Find more details about Metabolic Bacteria

-

>>

Unveiling the Role of Glucose Metabolism Bacteria in the Gut Microbiome: Insights into Metabolic Bacteria and Gut Health

>Exploring Fat Metabolism Bacteria: Unlocking the Role of Metabolic Bacteria in the Gut Microbiome

>Unlocking the Power of Protein Fermentation Bacteria in the Gut Microbiome: Insights into Metabolic Bacteria and Their Role in Gut Health

>Advances in Short-Chain Fatty Acid Producers: Key Metabolic Bacteria Shaping the Gut Microbiome

>Methane-Producing Archaea in Metabolic Bacteria: Unveiling Their Role in the Gut Microbiome

Unlocking the Role of Cholesterol-Metabolizing Bacteria in the Gut Microbiome and Metabolic Health

Read more: Metabolic Bacteria and the Engines Driving Gut Health in the Microbiome

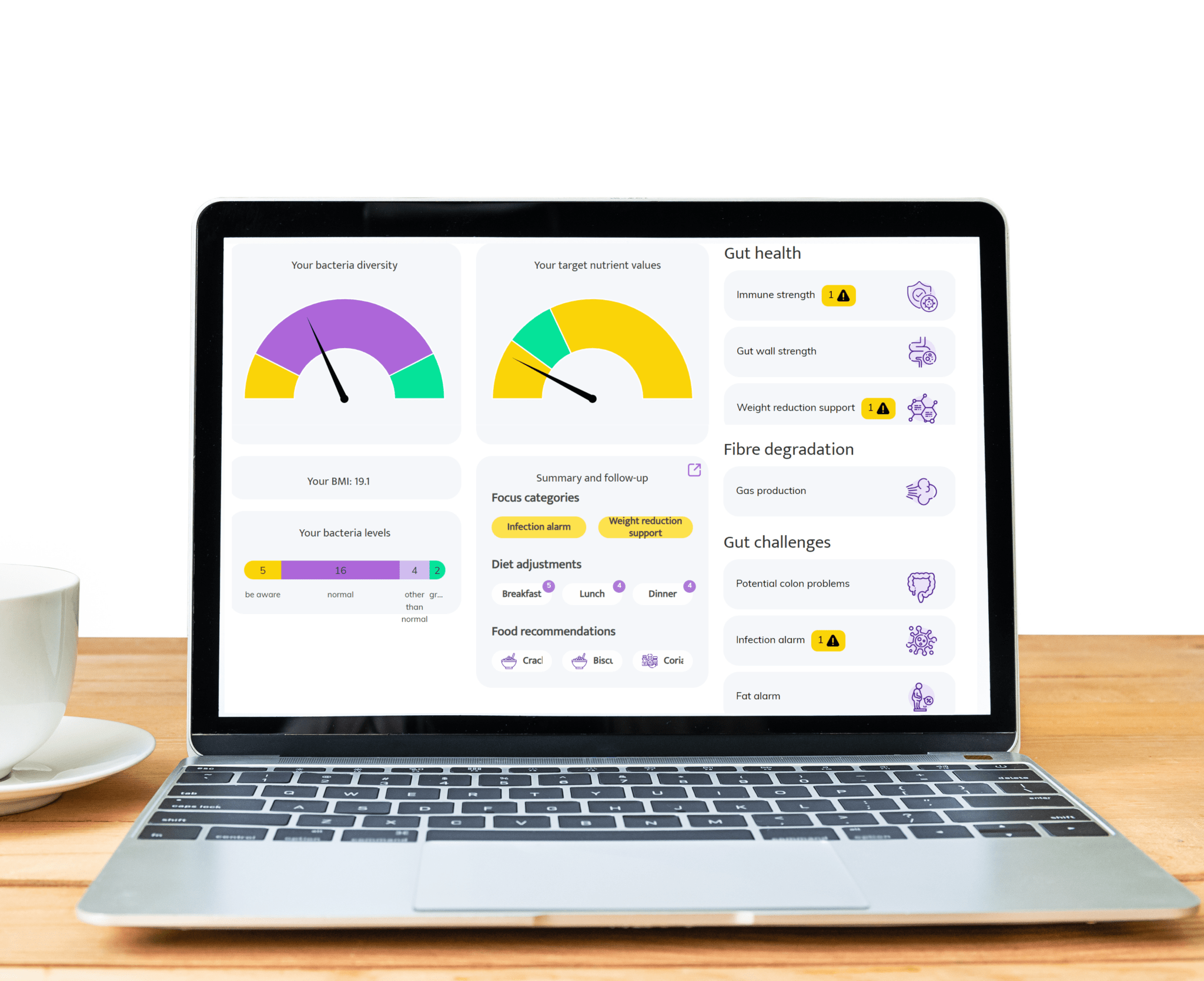

Areas where InnerBuddies gut microbiome testing can make a significant impact

-

Digestive Health

Gut discomfort like bloating, constipation, gas, or diarrhea often stems from an imbalance in gut bacteria. InnerBuddies analyzes the composition and diversity of your gut microbiome, identifying specific imbalances such as low fiber-fermenting bacteria or an overgrowth of gas-producing microbes.

By pinpointing the root causes of digestive issues, InnerBuddies provides personalized, evidence-based recommendations to support digestion. Whether through targeted diet changes, prebiotics, or probiotics, users can take actionable steps to restore harmony and improve GI comfort.

-

Immune Function

Over 80% of the immune system resides in the gut, and a diverse microbiome plays a key role in training immune cells to respond appropriately. InnerBuddies helps users assess their microbiome’s ability to support immune balance and resilience.

Low microbial diversity or the presence of inflammatory bacteria may indicate a weakened defense system. InnerBuddies delivers tailored suggestions—like anti-inflammatory foods or immune-supportive nutrients—to help build a stronger, more balanced immune response.

-

Mental Health & Mood (Gut-Brain Axis)

Emerging research shows that your microbiome influences neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, directly affecting mood and stress levels. InnerBuddies evaluates gut-brain axis markers to explore how your microbes may be impacting your mental well-being.

With insight into bacterial strains associated with anxiety, depression, or stress resilience, InnerBuddies can guide personalized strategies to help improve emotional balance—ranging from fiber-rich diets to psychobiotic supplements.

-

Weight Management & Metabolism

Certain gut bacteria can extract more energy from food and influence fat storage, insulin sensitivity, and appetite hormones. InnerBuddies assesses metabolic markers in your microbiome profile to help reveal how your gut may be impacting your weight.

With tailored advice on foods that support healthy metabolism—such as resistant starches or polyphenol-rich plants—InnerBuddies empowers users to make microbially informed decisions that complement their health goals and weight management strategies.

-

Skin Health

Skin conditions like acne, eczema, and rosacea are increasingly linked to gut imbalances and systemic inflammation. InnerBuddies analyzes your microbiome to detect patterns that may contribute to inflammatory skin responses.

By supporting gut barrier integrity and reducing pro-inflammatory microbes, the recommendations from InnerBuddies can help improve skin from the inside out—encouraging a clearer complexion and fewer flare-ups through gut-skin axis awareness.

-

Personalized Nutrition

Not all foods are beneficial for every gut. InnerBuddies delivers customized nutrition insights based on your unique microbial profile—identifying foods that nourish beneficial bacteria and flagging those that may trigger dysbiosis.

This personalized approach helps users move beyond one-size-fits-all diets and embrace gut-friendly nutrition strategies. Whether you’re optimizing for energy, digestion, or longevity, InnerBuddies transforms your microbiome data into actionable meal plans.

Hear from our satisfied customers!

-

"I would like to let you know how excited I am. We had been on the diet for about two months (my husband eats with us). We felt better with it, but how much better was really only noticed during the Christmas vacations when we had received a large Christmas package and didn't stick to the diet for a while. Well that did give motivation again, because what a difference in gastrointestinal symptoms but also energy in both of us!"

- Manon, age 29 -

-

"Super help!!! I was already well on my way, but now I know for sure what I should and should not eat, drink. I have been struggling with stomach and intestines for so long, hope I can get rid of it now."

- Petra, age 68 -

-

"I have read your comprehensive report and advice. Many thanks for that and very informative. Presented in this way, I can certainly move forward with it. Therefore no new questions for now. I will gladly take your suggestions to heart. And good luck with your important work."

- Dirk, age 73 -